Don’t ask a woman her age … and expect the truth

That boys lied about their ages to enlist in 1914 is common knowledge. Less well known is that women did too. This blog features two unusual women who felt age was no bar to ‘doing their bit’.

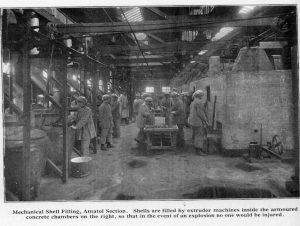

In 1917, Mabel Lethbridge was desperate to become a ‘mutionette’ and work in the Danger Sheds where highly explosive materials were handled; the minimum age was 18. A rebellious teenager, she was accepted at 7 National Filling Factory at Hayes Common. On her way to work on her first morning, she rather dismissed the comments of a woman in the bus queue who, hearing Mabel’s destination, comfortingly confided, this was “one of them terrible places … twelve months come Christmas I lost my eldest … all blowed to bits she was … we never got her body home.”

In Mabel’s Shed, dangers extended beyond high explosives. The machinery they were using to fill shells with amatol had been condemned over a year ago; replacements had arrived but were not yet operational. Soon disaster struck,

A dull flash, a deafening roar and I felt myself being hurled through the air, falling down, down into the darkness. A blinding flash and I felt my body being torn asunder. Darkness, that terrifying darkness, and the agonised cries of the workers pierced my consciousness. (Mabel Lethbridge Fortune’s Grass)

One of only two workers to be pulled out alive – at huge personal risk to the female firefighters who had fought their way into the blazing building, the catalogue of Mabel’s injuries makes grim reading: left leg severed, double fracture of the skull, right leg and thigh and both arms fractured, right foot badly broken, left ear drum destroyed (leaving her stone deaf in that ear), one lung damaged beyond repair, temporarily blinded by flame, hands badly burned, and huge emotional shock; a catalogue of injuries that match, even surpass, those sustained by many soldiers … and she was just 17. Having waited a year, when her ‘peg leg’ arrived, it had a right not a left foot. Unsurprisingly, many of these injuries had life-changing effects. The only other survivor suffered from what was undoubtedly Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Taken to what Mabel called, “a hospital more suited to the repair of her mental wreckage”, like many shell-shocked soldiers she never recovered her wits.

One of only two workers to be pulled out alive – at huge personal risk to the female firefighters who had fought their way into the blazing building, the catalogue of Mabel’s injuries makes grim reading: left leg severed, double fracture of the skull, right leg and thigh and both arms fractured, right foot badly broken, left ear drum destroyed (leaving her stone deaf in that ear), one lung damaged beyond repair, temporarily blinded by flame, hands badly burned, and huge emotional shock; a catalogue of injuries that match, even surpass, those sustained by many soldiers … and she was just 17. Having waited a year, when her ‘peg leg’ arrived, it had a right not a left foot. Unsurprisingly, many of these injuries had life-changing effects. The only other survivor suffered from what was undoubtedly Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Taken to what Mabel called, “a hospital more suited to the repair of her mental wreckage”, like many shell-shocked soldiers she never recovered her wits.

On 1st Jan 1918, Mabel received the OBE “For courage and high example shown on the occasion of an explosion during which she lost a leg and sustained severe injuries”, the youngest person to be so honoured. She lost a lengthy hard-fought battle for a pension and was merely awarded £1 a week through the Workmen’s Compensation Scheme. This, she was informed, she was fortunate to obtain as girls under 18 were not allowed in the Danger Zone!

Near destitute, she hired a barrel organ, which she played around the West End for queuing theatre crowds. Having again served during the Blitz, she died in 1968 from complications following her 50th operation.

In distant Australia, women heeded the Mother Country’s’ call to her Dominions. Not all the 2,562 Australian nurses who served overseas between 1914 and 1919 were the requisite 25-40 years of age.

Following the ill-fated 1915 Gallipoli campaign, alarmed at the horrific limb wounds and the extent of amputations, the Australian Army Nursing Service desperately needed more nurses, particularly masseurs (the initial name for physiotherapists), believing that massaging limbs might save both limb and life. Having already worked in London hospitals, masseuse Staff Nurse Esther Barnett applied. Born in 1857, she conveniently ‘forgot’ a good few years when completing the paperwork – perhaps Mathematics was not her strong point!

On 21st August 1915, Esther, 10 male and 6 female masseurs departed for Egypt; here these pioneer physiotherapists worked on up to 40 cases per day. It was not only those with severe limb wounds who benefited from the treatment. Shell shocked patients in total or near total paralysis responded well and quickly. Fifty-seven-year-old Esther worked for hours with perspiration pouring off her; orderlies regularly cooled her down with beakers of iced water and most probably the odd glass of spirits.

An unlikely seeming nurse, for in those days the nursing profession was rather a “stuffy” one, she drank her scotch straight, (“Scotch is for drinking, not bathing in”), did her talking the same way, played a mean game of poker and almost inevitably won. Even in the 1980s, former soldier patients remembered how she played poker late into the night keeping up the spirits of the youngsters … as well as drinking some of them under the table.

Her skill and dedication if not her drinking and gambling prowess, led to her being decorated with a civil humanitarian medal by George V. Having smuggled a hammer into Buckingham Palace she whacked a large lump of marble from one of the columns. Each of her grandchildren received a piece!

‘Mother Anzac’ briefly returned home in 1917, re-volunteering for overseas service in June 1918. Illness forced her to disembark in New Zealand. Originally reported as drowned, she was incorrectly named on the Australian Roll of Honour of War Dead. She subsequently worked amongst the Maori tribes, falling victim to the Spanish flu pandemic. The Maoris buried her, a blackberry bush marking her grave and preserving her indomitable spirit.

We Also Served: The Forgotten Women of the First World War

We Also Served is a social history of women’s involvement in the First World War. Dr Vivien Newman disturbs myths and preconceptions surrounding women’s war work and seeks to inform contemporary readers of countless acts of derring-do, determination, and quiet heroism by British women, that went on behind the scenes from 1914-1918. In August 1914 a mere 640 women had a clearly defined wartime role. Ignoring early War Office advice to ‘go home and sit still’, by 1918 hundreds of thousands of women from all corners of the world had lent their individual wills and collective strength to the Allied cause. As well as becoming nurses, munitions workers, and members of the Land Army, women were also ambulance drivers and surgeons; they served with the Armed Forces; funded and managed their own hospitals within sight and sound of the guns. At least one British woman bore arms, and over a thousand women lost their lives as a direct result of their involvement with the war. This book lets these all but forgotten women speak directly to us of their war, their lives, and their stories.

Reblogged this on The Owl Lady.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Viv 🙂 x

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog and commented:

Lest we forget those who served at home

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure Cathy 👍😃

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hurray. Sounds a fabulous read. Bravo for these gutsy women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely!

LikeLiked by 1 person

XX XX

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fabulous post! Sounds a great read. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Judith. Glad you enjoyed it x

LikeLike

This sounds like an amazing book.

LikeLiked by 1 person